London: Day 3

My third day in London was full of ups and downs, and a hard pill to swallow!

It was not exactly a case of ‘three times a charm.’ After this article—the third in my London/Paris series—you might think my third day in London was the opposite of charming. If you were only focused on the negative aspects, you might even say it was a disaster. I feel like I learned a lot from that day. I did some growing, that’s for sure.

It began quietly enough. I left my suitcase in the hallway outside my room on the eleventh floor. It was the time for it to be collected and put on the train to Paris ahead of my own arrival. As advised by Natalia, I had my overnight bag to get me through the weekend. Here’s a little passage from my travel journal to give you some idea of how peaceful the morning was:

Looking outside my window:

…a tiny white bird went flapping down Wilton Road, flapping along down the middle, toward Knightsbridge, I suppose. White as snow. Instantly thought of Mama because she always notices the birds. I don’t know what to call the bird. ‘Mama bird,’ why not? The Mama bird reminding me of the love that awaits me at home.

The night before, I had secured reservations for a tour of Kensington Palace (Saturday, this day) and for the Louvre in Paris on Monday. For this day, I had it all planned out from sunup: Walk around Westminster and St. James, tour at KP, and if I felt up to it, get back on the tube and go to Bloomsbury, and just do whatever—Sherlock Holmes Museum, Charles Dickens Museum, British Museum? Or just walk around and play it by ear.

I must have altered the plan in my head while I ate breakfast in the hotel’s restaurant because I ended up taking the tube to Russell Square. Right outside the station, there was the “Bloomsbury Coffee” bar. It was such a quiet, peaceful morning. A little wet and chilly, but so serene. It’s hard for me to pass up coffee, especially when it is being served in such lovely and quaint surroundings. The young man working the machines (he was working alone) was calmly processing a modest procession of orders. There were (maybe) two people waiting ahead of me, and no one behind me, and all of us were patient and pleasant, putting absolutely no pressure on the young man. The demeanor of the barista was, in fact, so calm and efficient, I doubt even an impatient customer or two could rattle him...much. I ordered a hot chocolate and paid with my phone. (I rarely used Apple Wallet before in America, but in London I quickly caught on to the convenience of this tool, as it was much easier, and felt safer, to pay with the phone rather than dig around my purse for my wallet, pull out the wallet, etc. And I had the Apple Pay set up to default to the zero-interest credit card I had secured expressly for this trip, one that did not charge a foreign transaction fee, and which I planned to pay off right away on my return to the States.) Hot chocolate and phone in hand, I walked down Bernard Street and turned left on Herbrand Street. At the corner of a cobblestoned alley called the Colonnade, something caught my eye: The Horse Hospital. I took a photo of it for horse-loving Mama. Following Google Maps (telling me how to get to the British Museum) I turned back up Herbrand Street, left on Bernard, across the road, through the park at Russell Square…. I emerged from that picturesque park at an intersection that can only be described as a street I could still see Virginia Woolf or Oscar Wilde hurrying along—umbrella out, or in Oscar’s case, not out but closed, and twirled nonchalantly while he smoked. Montague Street—with the brown brick and the black doors built into white facades, and the checkered steps going up to the doors, and the black railings around tiny balconies, some of which had little trees and red flowers growing in pots.

Britain has a lot of museums and countless exhibitions—something about everything and for everyone. The British Museum, like the Louvre in Paris, truly encapsulates, incredibly, the breadth of human history in all its infinite expressions. In recent years, the British Museum has come under fire for its housing of artifacts that were stolen from former colonies. I read a lot about this issue in library school and have come to feel that the reality is far more nuanced. Of course, it’s true that ‘British’ is really a misnomer for this house of global treasures, and there are strong arguments for items to be repatriated. Nevertheless, it’s hard not to appreciate the tremendous expense and hard work invested by the museum toward the preservation of all of it. I really do feel that the British Museum does an extraordinary job of acknowledging the truth of the past; they don’t deny any of it, but they do elevate beauty and creativity to a level where it can be exposed to everyone’s advantage. When I think about what might be lost and how much is gained by the efforts of the British Museum, I feel an overwhelming sense of awe and gratitude and my words fail me. You might wonder why I don’t care about the Harrods perfume hall—mentioned in the previous article; it is because, or rather, one of the reasons is that I care about this—see video below:

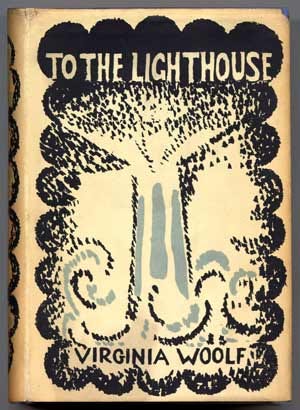

If I had stepped the opposite way from Russell Square Station, I might have bent my steps toward the Charles Dickens Museum. Then, I would have passed by Brunswick Square, a place that repeat-readers of Jane Austen’s Emma will recognize. Another place you can walk to from Russell Square Station is 52 Tavistock Square. Virginia Woolf lived there with her husband, Leonard Woolf. There’s not much to see, sadly, for it is now the Tavistock Hotel, with only a plaque acknowledging that the great author lived on the site, but, as with so much of London, the area is great for walking, and one certainly senses the ghost of Virginia in these streets. Definitely, do take a turn into Tavistock Square Gardens and don’t forget to look in there for the Bust of Virginia Woolf—1882-1941. You could spend a lifetime in London and still find something everyday you never saw before.

From the British Museum, I walked down Great Russell Street, Bloomsbury Square, and down to Holborn Station. That’s when I got back on the tube because my date with Kensington Palace loomed closer. I got on the Central Line and stepped off the train (minding the gap) at Queensway. That put me right on the spot I needed to be in….I excitedly crossed the street to enter Kensington Gardens. I walked straight, along the wide main pathway, ‘the Broad Walk,’ taking care to notice the small stuff—walkers in small groups, solo joggers, lots of tourists, some of them on rented bicycles, but, as it was a Saturday morning, there were also parents out with their kids. When I saw the Round Pond up ahead, I knew I was near the palace. There were lots of people taking selfies and group selfies in front of the Queen Victoria statue. I walked straight past them to the palace entrance. It was not open yet, and there were just a few others milling around, but it was obvious what I had to do from two signs set down near the entrance—one was for queuing for the 10 o’clock tour, the other for the 10:30 tour. I was on schedule for the former, so I stood there behind a couple, the only people ahead of me. I mentioned John van der Kiste in my previous article. From reading some of his books about the Hanoverian monarchs, I knew a bit about the kings and queens who had lived in Kensington Palace—Queen Mary II (in fact, a Stuart) and her husband King William III, her sister Queen Anne, and the Hanoverian Kings George I & II, and II’s consort, Caroline of Ansbach. Those are the monarchs who dominate the story in the State Apartments. The Victoria Rooms are another matter. This is where you learn exclusively about the life of the queen-empress who was born in the palace and lived there almost as a prisoner—well-cared for, certainly, but closely guarded because of her precious position as heir to the throne. Once Victoria was an adult who could make her own decisions, she left KP and never looked back, so ever since her time living there, the palace basically became the ‘aunt heap.’ Prince Philip’s grandmother, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria also named Victoria, lived there as a widow, and long before Philip married the future Queen Elizabeth, he visited his grandmother in the grounds of KP. Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone also lived there; by birth, ‘Princess Alice of Albany,’ she was another granddaughter of Queen Victoria; she is mentioned in my previous article, and she lived at KP until her death in 1981. In the 20th century, the biggest-name royals to live there were Princess Margaret and Lady Diana, Princess of Wales—née Spencer. In this century, we know it to be the official London residence of Prince William and Catherine, the current Prince and Princess of Wales, but they apparently spend very little time there since they have other more homely residences in the country which their family prefers for the privacy denied them at KP. A few other royals have lived at KP in recent years—second-rate royals like Prince and Princess Michael of Kent, for sure, but also more prominent ones like Prince Harry & Meghan, before they moved out to live at Frogmore Cottage1 near Windsor Castle; Princess Eugenie and her husband, Jack Brooksbank, before they too moved out to take Frogmore Cottage after Harry & Meghan moved to California; and the Duke of Kent, who Harry mentions in passing in his memoir, Spare. Apparently, when Harry would smoke pot behind his KP cottage (‘Nott Cott’) the smoke would drift over into the Duke of Kent’s garden. So yeah, that’s KP these days—some historical State Apartments and showrooms in the front, and offices and apartments for mostly minor royals (and royals who became ex-royals) and retired staffers in the back. I thought it was cool, though. On Facebook, I got a lot of likes on my photos of the King’s drawing room (yes, photos are allowed in KP, unlike at Windsor Castle) but for me the most impressive things were the King’s Staircase, the Wind-Dial in the King’s Gallery, the Diana wallpaper in the passage that led to the public WCs—I mean, even the water closets were nice, lol—and the Sunken Garden, with its rectangular pond and a statue of Diana, Princess of Wales. Of course, I was as awed as everyone else by the Queen Victoria jewels in the “Victoria Rooms,” and I was especially impressed by the historical discoveries made in the study of royal servants and the involvement of British monarchs in the slave trade. There are several incredible stories that have been uncovered by the HRP historians—like the one about “Peter the Wild Boy,” and the tragedy of Gustavus Guydickens, who died in a debtors’ prison in 1802 after being arrested for allegedly having sex with another man in Hyde Park. (Below, I’ve embedded an instagram post from artist Matt Smith that shows off the exhibition of the plates that depict the story of Gustavus Guydickens; and two episodes from the HRP podcast on Apple Podcasts relevant to what I saw at KP.)

The statue of Diana was dedicated in 2017, 20 years to the day after her death. According to the website of Historic Royal Palaces, the statue, showing Diana and three children clinging to her, represents the “universality and generational impact” of her legacy. A covered walkway surrounds the garden and there are several ‘looking’ points set into each side. When I approached the garden, there were people clamoring to take turns (and take selfies) at the first one, on the side of the approach from the palace, where you have a head-on view of the statue. Most of them were satisfied with that one perspective. I was drawn to go deeper. I walked around it slowly and listened. It was quiet up there, quite set apart from the palace shop and cafe below. (Sunken Garden might have given you the impression that it is somehow stepping down from the palace level, but no. You have to walk up some steps to get to it. The ‘sunken’ in the name comes from the fact that you have to step down into it, although no one can actually do that because it is closed off. The ‘cradle walk’ that wraps around it is one’s only access to it—unless, obviously, you’re a VIP like the members of the royal family who live there. Diana and the nondescript children depicted in the statue are quite alone there, impervious to the outsiders who peak in; they share the beautiful garden with the birds who fly in and the roses who grow from its soil. Five varieties of over 200 roses grow there, according to the HRP website, along with dahlias and sweet peas and tulips and forget-me-nots. The anonymous poem “The Measure of a Man” is inscribed in the plaque in front of the statue. It is slightly altered to use the feminine pronoun:

These are the units to measure the worth

Of this woman as a woman regardless of birth.

Not what was her station,

But had she a heart?

How did she play her God-given part?

There is something so vulnerable about this little paradise, protected but also exposed, where the public has access but only to look in. It seems to me a perfect analogy for Diana’s life. Alone but always watched. Seen but not touched? As I walked around it, I forgot the world beyond. There was only this spot, right now, the quiet and the perfection. After I covered the four points around the garden, I followed the path in front of the Orangery—a restaurant where they serve breakfast, lunch, and afternoon tea, with discounts for HRP members—and then I took a shortcut back to the Broad Walk and kept going to walk around to the side of the palace—the famous side, with the iron gate and the King William III Statue. That path is called the Studio Walk. I walked through the little opening in the wall. To the right, there was the guarded gate that leads to the private parts of the KP complex (compound?) and the Palace Green, a place for helicopters to land. In the little walkway behind the wall, connecting this private gate and the main road, is where I found the Forest Bike that got me into trouble. There are tons of dockless bicycles all over Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, with QR codes for paying and riding. I was taken off guard as it zoomed forward and lost my balance. I ‘caught’ myself on a little white fence right there in the Palace Avenue. It happened so fast and, while I did hurt my arm, I wasn’t really cognizant of the pain yet. I was just thrilled to be zooming around this awesome park. I did my best to mind the ‘no cycling’ points. (The go-ahead-and-cycle points are mostly in the broader lanes and the dedicated bicycle lanes on the perimeters.) I had no idea where Kensington Gardens ended and Hyde Park began. To me, it seemed all the same park. I zoomed past the Albert Memorial. They had some sort of protest going on that day, probably about Gaza, but who knows? I rode down the Carriage Drive, past the Serpentine Gallery, and over the Serpentine Bridge. Is that the dividing point between KG and HP? I think so. I think I followed West Carriage Drive all the way around to the Victoria Gates. There was a traffic jam. It was bumper to bumper. (This, I later learned, was due to road closures and the protest that was happening.) I think the street name changed to Bayswater Road at that point. So I went through the gates, back into the park, then back through the gates again after I saw a ‘no cycling’ sign on that path, and basically rode back the way I had come—but on the opposite side, minding the British way of riding on the left, lol ‘wrong’ side. I was determined to follow the rules and kept imagining how awful it would be to be scolded by a police officer, fined, or arrested. I mean, not only would it be embarrassing as hell, but, oh Lordy, what a hassle!

Once I was back over the Serpentine Bridge, I began to consider getting off the bicycle. I left it on a little path near the Serpentine South Gallery because I wanted to look at the outdoor contemporary art in front of the gallery. This pavilion designed by Minsuk Cho was very interesting. You could sit inside it, as I did, and just absorb the quiet and the serenity; it is a place of curious sounds, where instruments blend with nature, and people are quiet—I saw one or two people sitting there reading books. There’s a little bookshop too. ‘The Library of Unread Books’ is a contemplative space for books the donors ‘for some reason did not read’, the unread book that sits on a shelf. Visitors are welcome to pick up the books and “read on their behalf.” The books lay flat and stacked on the shelf, just like Karl Lagerfeld appreciated, so that you don’t have to turn your head to read what’s on the spine.2 In retrospect, though it did not occur to me at the time, the whole Korean-inspired pavilion at the Serpentine South Gallery reminds me of our own City Park Gallery in Baton Rouge.3 I know it’s absurd to compare our little Baton Rouge Gallery to the Serpentine Gallery in London, but there are striking similarities: both small galleries, with contemplative surroundings, free and open to the public, a tiny refuge amid the wider chaos.

From the Serpentine Gallery, I walked back out to Carriage Drive and turned up toward Kensington Gore. I walked along that road that is dominated by the incredible Royal Albert Hall. It was so quiet, hardly any pedestrians and no cars, just some police officers. Whatever protest was going on that day had necessitated the blockading of roads around the park so that even bus traffic was interrupted. I later learned that these protests were predominantly about the war on the Gaza Strip, but apparently there were other movements attaching themselves to it. Somewhere on the Prince Consort road my arm began to bother me. I thought with dread of having to spend my last day in London in a clinic. It wasn’t broken, that was obvious, but it was painful. I began to think about getting back to the hotel and putting some ice on it. But finding a bus to take me back was challenging due to the street closures. I briefly considered getting on another Forest bike (since I already had the app for it) and peddling back to the hotel. I quickly rejected this as a foolish plan, given that I’d be on a bicycle peddling on the ‘wrong’ side of the road with only one good arm. I knew which direction I needed to walk—up Kensington Gore, between the Royal Albert Hall and those well-proportioned red-brick Albert Hall Mansions, down Prince Consort Road. I didn’t know it, but the place where I entered the Underground (at the Science Museum) took my unknowing self down a ridiculously long passage to South Kensington Station. I recorded in my journal that I rode the tube for two stops before Victoria Station. I got a bucket of ice for my arm from the bar at the hotel, took some Advil that I already had, and fell asleep. Later, I went to a pharmacy in Victoria Station and bought some heating patches so I could alternate heat and cold on my arm. I walked down Buckingham Palace Road to Elizabeth Street, turned left and down Hugh Street. There’s a sushi place called Sanjugo at the intersection of Hugh and Cambridge Streets. That’s where I turned back and walked through the enormous shopping mall in Victoria Station to get back to the hotel. I was pretty depressed about my arm. In the hotel, I comforted myself by watching two favorite movies: A Room with a View (1985) and Northanger Abbey (2007). Natalia brought me some cakes from the afternoon tea I missed; she also brought an embrocation for me to try on my arm.

My room had a window, and so I had a view of sorts, but it certainly was not Lucy’s or Miss Bartlett’s idea of ‘a room with a view.’ I suppose in my scenario the object would be the Thames, not the Arno, or perhaps Big Ben or the London Eye. The view I had was actually very nondescript, but I felt more like old Mr. Emerson when he said he already had the best view, the view inside, meaning his heart. The view was also better eleven floors below—well-rounded, all around me, on the street, on the tube, and in the park. And that bird flying by my window? That wasn’t magnificent because of what the bird was flying past, but because of how the bird made me feel.

A Room with a View and Northanger Abbey are both stories about strangers. Forster’s heroine is an English girl abroad for the first time, learning about honesty. Austen’s heroine is an English rustic in the ‘big bad world’ (of Bath) for the first time. Lucy wanted exploration, and to be allowed to play Beethoven with as much vigor as she felt. Catherine, the heroine of Northanger Abbey, wanted adventure, just like in the novels that she loved reading. When Lucy ventures out in Florence alone, she ends up witnessing a murder. That’s not exactly the kind of adventure she hoped for, but it is exactly the kind of adventure that Catherine imagines in Northanger Abbey. Both heroines have a lot to learn about the ways of the world. Lucy had to learn to stop lying to herself and to others; she’d only begun doing that because she wanted to please the world, but the lies had become toxic to everyone she knew. One impolite truth in the beginning is better than a lifelong web of deception pointed at both ends. And Catherine had to learn that life is not a Gothic romance novel. Catherine was so ashamed of herself, for letting her overactive imagination cloud her judgement. As I sat there in my hotel room, watching favorites movies based on favorite books, I felt ashamed of myself too…. I’ve known how to ride a bicycle since I don’t even remember what age, and as an adult in the 21st century, I’ve ridden quite a few eBikes. But somehow, of all the rides I’d taken on ‘ride-sharing’ bikes, it had to be the one in London that resulted in a mishap. Was it just the price one pays for adventure? Many people go through life never doing spontaneous things for this very reason—to avoid the kind of thing that happened to me in London. One misstep, one moment being taken off guard, and now you’re icing your arm in a foreign city. Lucy tried to live in the perfectly cautious, calculated way. Imagine if Catherine Morland, the heroine in Northanger Abbey, had behaved like every other cautious, pretentious, ambitious lady? Henry would never have seen her heart.

I went to bed hoping that Sunday (Day 4 of the tour, Day 1 for Paris) would be gentler.

Footnotes

Not to be confused with Frogmore House, Frogmore Cottage is much more modest and has been in the headlines a lot ever since Harry & Meghan decided to give it up.

That’s a reference to my article “The Angel in the House,” my ode to the writer Virginia Woolf and those persistent enough to read—and finish—her works: