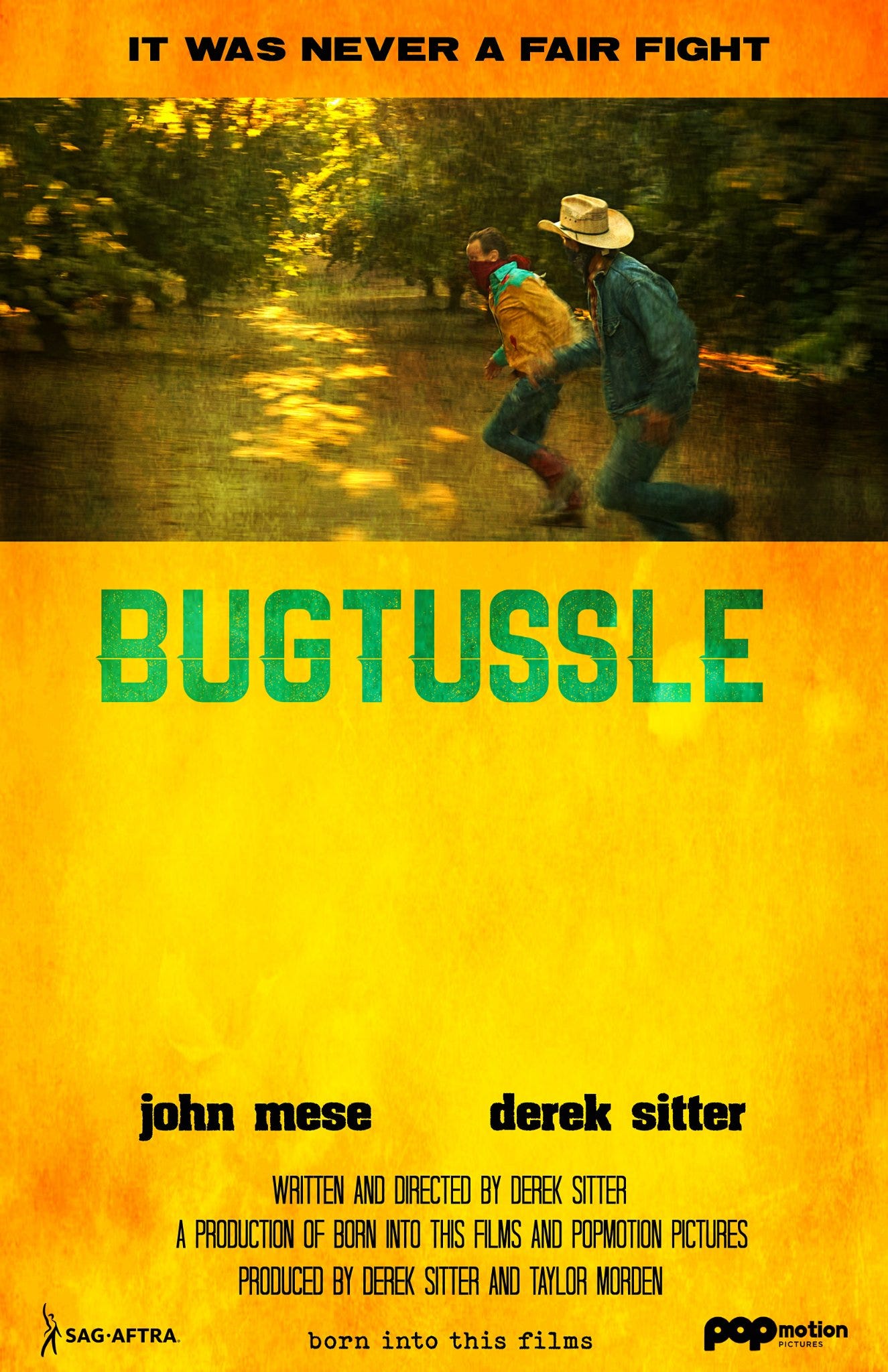

I didn’t know until I googled it that “Bugtussle” was the town from whence the Clampetts loaded up the truck and moved to Beverly. That makes it a perfect title for director Derek Sitter’s latest film. Coyote (played by Sitter) and Crow (John Mese) are failed bank robbers on the run who dream of a better life, as owners of the “best bowling alley ever” and money to buy beachfront property in Beverly Hills. They want to be Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and they might pull it off if Coyote wasn’t such dead weight for Crow. After Coyote shoots the bank teller and gets himself shot in the abdomen, the pair hightail it through the woods until they find a shed to squat in. We learn later that Coyote shot the bank teller because her incessant talking annoyed him. Coyote is just not cut out to be Bonnie or Clyde. He’s a loose cannon, and he can’t even dress discreetly. Crow tells him he looks like “Conway Twitty on crack.” Their relationship is vague. One can’t help wondering how these two got to be entangled. Are they brothers? Crow refers to Coyote’s father in a dissociative way, so maybe not. But if they aren’t brothers of the blood, there is a kinship somehow. They are bound together in a permanent and pathetic way. There are strong echoes of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. In his treatment of Coyote, Crow vacillates between affection/consolation and anger/desperation. “Jesus Christ, I need a drink,” he says, leading to Coyote revealing for us that Crow is a recovering alcoholic. After Coyote’s next disastrous blunder, Crow totally falls off the wagon, grabs a canteen of rye whiskey, and chugs it like there’s no tomorrow. He tries to keep “Coy” calm, but Coyote is very anxious, jumpy, reactive. Storytelling works, but only temporarily. Crow elucidates on their California dreams: they’re gonna take the money they beg, borrow, or steal and buy a bowling alley, live in Beverly Hills, rides horses on the beach, and eat T-bone steak everyday. Their dreams have boyhood stamped all over them. They are men who never got to be boys, after all.

My favorite part is when Crow falls off the wagon. I know it must sound awful of me to favor this, a man’s lowest point, but honestly, in the entirety of this 21-minute film, this is the meat. This is the juice. Crow downs the whiskey and calls the situation what it is—a curse. A shit show. By revealing what he feels he is missing out on, he reveals his soul. He wants what everyone wants—to be loved, to be at peace, to be calm. That’s what “house and kids” ultimately means. Security. Permanence. It means not being on the run. It means not having to deal with Conway Twitty wannabes on crack. “I could do anything I want, but you always f—k it up.”

“I love you, Crow. I mean, a normal way, not a weird way.”

There it is. Why Crow and Coyote are bound together. Why Crow is stuck. “A no-good drunk who will never amount to a goddamn thing,” quoting his old man. “It wasn’t a fair fight.” (He takes a drink.)

“Why does everyone have to be so mean?”

“You can’t trust nobody.”

Not even a brother, or no one but a brother? To give up everything for Coyote, the way Crow did, it is nothing short of a brother’s love. Mama said it: “There’s no bad seed, only bad dirt.” It wasn’t a fair fight.

The movie, which is 21 minutes long, just won Best Editing and Best Music at the Indie Shorts Magazine Film Festival.1 It was nominated (but did not win) for Best Short Film and Best Director.2

My review:

Acting and direction: Riveting, intense, connected, beautiful—5*

Cinematography: Simple and clean—5*

Screenplay: Realistic, descriptive, packed with emotion—5*

Editing: Appropriate length, everything that’s needed, nothing more, nothing less—5*

Music: Sets the tone, anxious, riveting, fast-paced—5*