I feel like this article needs a disclaimer, or warning. It’s about the magic of life, especially the magic which we connect with during the Christmas holidays, but there are also many “adult” references in this journey. I guess it all ties into the history of people trying to figure things out. The Grand Albert touches on questions that hit to the core of what it means to try to get through daily life. I don’t like to be ageist or presumptuous in deciding what is appropriate for kids. The conclusion of this article taps into the magnificent wonder and innocence of childhood. The path is just a little twisty.

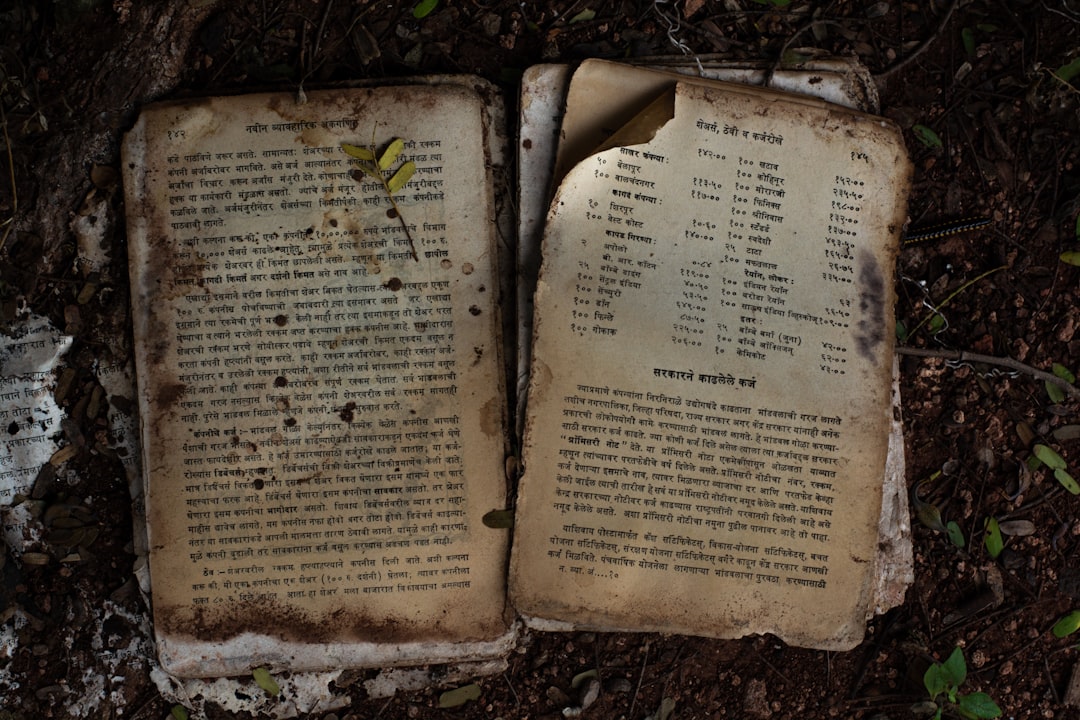

I know I’m not the only one thinking either of the future or the past as we approach the end of 2022. I think a lot of us tend to look back on the year, a ‘year in review’ as it were—places traveled, books read, memes laughed at, new things tried, new skills, new friends? I’m looking a lot further back, much further than my own lifetime. I’m looking back to the Middle Ages as I clutch the English Edition of The Grand Albert, edited and translated by Edmund Kelly. This little book of medical, spiritual, and practical advice was written by we don’t actually know who in the 13th century. “Albert” was probably not one person but rather an assortment of people, monks most likely—nerdy friars who were into all sorts of shady things like alchemy and astrology. Check out the Wikipedia page “Grand Albert.” Yours Truly wrote it. I created the article in 2019, and since that time, it’s been expanded by others. Looking over it now, I feel like I could add quite a bit about what the Grand Albert is all about. What fascinates me about the Grand Albert is that it tries to answer questions that every human has ever longed to know. It speaks of women, about women, from a man’s point of view. Woman did not have a voice then. The pen was in the mens’ hands. Women were busy washing clothes in the river, giving birth, being midwives, nursemaids, or themselves recovering from disease. She was an object of study to the men who struggled to understand her mood swings. “Albert” proposed that a number of planetary factors were behind feminine moods.

In the first of four volumes, the Grand Albert monks consider how astrology guides the menstrual cycle and also what is happening at the celestial dimension to effect conception and pregnancy. The “power of going and moving”1 begins at the fetal stage, and “Albert” proceeds to walk us through the development of the fetus. The planets guide every stage, they wrote—from discerning Saturn, to generous Jupiter, angry Mars, then: “The dominant Sun in the fourth month [of pregnancy] prints the different forms of the fetus, creates the heart and gives movement to the sensitive soul,” although they acknowledge that Aristotle differed in his belief that the heart was actually the first part of the fetus to develop, and still “others” opined that the Sun was the source and origin of all life.2 The Sun, opined the writers of the Grand Albert, influences the development of memory; the Moon, they said, fortifies us with the natural virtues. Each sign of the zodiac, too, dominates particular body parts. Aries, the most “noble,” lies at the head, the point of reason. “Taurus dominates the neck, Gemini on shoulders, Cancer on hands and arms, Lion on chest, heart and diaphragm; Virgo on the stomach, intestines, ribs, and muscles.” Scorpio has to do with sex drive and genitalia; “Sagittarius nose and excrement, Capricorn knees and what is below; Aquarius thighs;” and finally, the reader is informed, Pisces is about feet.

Chapter VII of Book I goes into ways to determine if conception has occurred. It says if a woman is horny all the time (not in these words, but clearly enough) she is likely pregnant, although, amusingly, Albert does concede that strong sexual desire is not exclusive to being with child. Yet rosy cheeks and a strong appetite for “apples, blackberries, cherries” are “in a few words, the most common signs of conception in women.”3 These men who called themselves Albert had much to say about reading the signs in women, for example, how to tell if a woman was chaste. The reader is warned that some women are sly and know how to trick you into thinking they are chaste! The Grand Albert also warns their readers about old witchy women, who no longer menstruate, and have bad intentions toward children!

There is a lot of superstition in the text. For example, if you’re having trouble conceiving a child, the advice is to try wearing a goat’s hair belt that has been dipped in donkey’s milk. Book II covers the meaning behind precious stones, how to acquire the traits and virtues of animals, such as the courage of a lion—just wear its eyes under your armpits!4 (I wonder how many of the Grand Albert’s medieval readers actually, in their quest for courage, plucked the courage to acquire lion’s eyes!)

Much of Book III is like Harry Potter in Potions class. The monks talked about using “burnt snails and bush mulberries (pulverized)”5 to cure dysentery. There’s an anti-aging potion on page 239. All you have to do is take some small lizards, the horn of a deer, white wine tart, white coral, and rice flour; stir it all together in a mortar, throw in some in some slugs, flowers, and add broth. Then let it soak overnight in distilled water. When you wake up, mix in lots of white honey and grind it well with a pestle. Preserve it in a “vessel of silver or glass which is very clean.”6 When ready to apply, rub it in on the face, hands, chest, and throat.

Please don’t try this at home. This text was cobbled together, in Latin, by curious, rebellious, and naughty monks between 1245 and 1493; they had to write it in secret, in between regular duties, Mass, meditation, and Gregorian chant. It was forbidden by the Church and, therefore, published and disseminated in secret. Like other grimoires, it was popular among a highly superstitious public who also had a practical interest in remedies for diseases. (Book IV, Chapter III is wholly about natural and alleged remedies for fevers. Also in Book IV, there is a chapter on physiognomy, the study of how facial appearance corresponds to character.) By 1703 there was enough interest to make a wider-market French translation profitable. Of course, superstitions, astrology, and magic are still immensely popular. Not only are the Harry Potter books the bestselling and most translated works of all time, making author JK Rowling a billionaire, the character Severus Snape, Potions master, is one of the books’ most beloved characters; and in these books we find magic in its most compelling forms—not least the use of a wand, a swish and flick, to light the path and make daily chores a little bit easier; or the brewing of a love potion to entice the attention of a celebrity crush! Witchcraft and sorcery are staples of pop culture that, despite resistance from evangelical religious groups, continually transfix most of us. Magic brings hope that we might solve our problems and make daily life more delightful.

Most of us do not actually believe in Santa Claus; yet we still celebrate the magic of giving gifts every year. Even if we only “believe” in Santa as children, there is something about it, a yearning, that lingers into adulthood. It’s the magic of the idea, or perhaps the magic of the memory, which we live again and again, every time we watch our favorite Christmas movies. I don’t doubt this effect is magnified if you have children. You relive the magic through the wonder in their eyes and on their faces. The Grand Albert talks about the magic of what we don’t necessarily see, but of what we feel and sense in other ways. Producing enchantments by waving a wand is an imaginative and enticing idea, but the real magic lies in the changes we can effect by our passions—for good as well as for evil! “All that is called marvelous and supernatural,” it says, “and which is vulgarly called magic, comes from the affections of the will, or from some celestial influence at certain peculiar hours.”7 The effects we can manifest by our passions, or by the intensity of our focus, are common themes in “New Age” literature. It is well known that “faking a smile” can put you on the same level of vibration as a genuine smile. It opens the pathway. It relaxes the facial muscles, and further relaxation follows. It gives you the opening to take a deep breath and chill out. As I read Book II, I couldn’t help thinking about Esther and Jerry Hicks. In case you’re unfamiliar, Esther Hicks is a channel for spirits collectively known as “Abraham,” who communicate through Esther. “Abraham Hicks” is an empire of motivational materials, lifting vibrations and giving people courage to dare to dream. In a nutshell, they remind us that whatever you are putting your attention on is what you are going to get more of. If it’s hatred, you’ll get more hatred. If you’re walking around feeling anxious, you’ll attract more things to be anxious about. That’s basically what the “Grand Albert” says too; they add to it the celestial dimension—what the solar system and the planets are doing. By “excessive inclination,”8 (or what Abraham Hicks calls the intentional vortex) you can shift what’s happening in your body at the cellular level. It all boils down to the Law of Attraction—a very popular concept in the 21st century. The difference, of course, is that Abraham Hicks and our modern-era spiritual teachers are not advising us to (literally) take and wear the eyes of the lion if we want courage. If you want to feel courageous, think of what makes you feel that way. Have fun with it. Make it into a game. Think about that time you did something terrifying (like make a speech in front of a crowd) and it turned out all right—you got applause, people enjoyed what you talked about, and you felt a boost of energy. You were terrified, but you did it anyway, and you survived; and it made you feel… good, because you thought, “Hell yeah, I can do this.” What is superstition other than something we do to “fake it” in order to “make it,” or just psych ourselves into not being afraid? That rabbit’s foot keychain just gives us something—a sense of doing something, a sense of power—to hang onto. Superstitions and the placebo effect—these things do have an effect, but it goes deeper than just wearing a shark’s tooth, clutching a crucifix, or swallowing a pill. It gives you comfort. Even swallowing the pill makes you feel you’re doing something, and that alone improves how you’re thinking about your situation. The “luck” or “good fortune” comes out of that feeling of taking control. What you feel and what you focus on is what you bring into your vortex, to borrow the terminology deployed by Abraham Hicks. Whatever you do, just try to have fun. Fun is at the heart of making magic in life. The whole reason everyone, to some degree, celebrates the Christmas holidays? It’s not only devout Christians who get excited about the “ho, ho, ho.” We love the awesome lights, the crazy nights, and the pumpkin spice lattes. We love the music and the corny movies. The magic is in how all that stuff makes you feel. Everyone, no matter what his or her religion, connects with George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life because it’s a story that everyone lives—the story of coming to terms with what gives our lives meaning. In a sillier way, I think, Fred Claus gets to the same heart of the matter. We all know something of living in the shadow of something else—it’s the little tree growing up in a big forest and yearning for sunlight. Sometimes the magic is realizing that the little tree is doing its part in its own way.

Linus said in the Peanuts classic, it's not such a bad little tree. “Maybe it just needs a little love.”9

[There are some chapters in The Grand Albert which I did not mention above, but they happen to be ones that I would like to come back to for a future article. These are: The Wonders of the World by Albert the Great, a treaty in the Book II, and Happy or Unhappy Days, Chapter II of Book IV.]

The Grand Albert, p.27. Edited and translated by Edmund Kelly. © 2013-2019 Dark Arts Publishing.

The Grand Albert, pp.34-35.

The Grand Albert. p.78.

The Grand Albert, p.153.

The Grand Albert. pp.249-250.

The Grand Albert, p.250.

The Grand Albert, p.174.

The Grand Albert, p.173.

A Charlie Brown Christmas (TV movie 1965). https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0059026.